Being a translator, and especially as a legal translator, I am acutely aware of the fact that the word “omertà” is practically untranslatable. It is often expressed in English as “code of silence” but this fails to convey the deeply ingrained social attitude born out of a mixture of fear, distrust and feelings of helplessness inherent in the word. This piece attempts to explain what omertà is and how it works in Sicilian society.

There are two conflicting opinions on the origin of the word: one says that it comes from the Neapolitan “umertà,” meaning “humility,” giving it the sense of an attitude of submission; the other denotes the Spanish word “hombredad,” or “virility,” as the origin, suggesting it is indicative of the behaviour of a “real man.” These two apparently contradictory definitions are, however, both intrinsic elements of the phenomenon. You must be both humble enough to submit to the rule of omertà and, at the same time, tough enough to maintain omertà whatever pressure is brought to bear on you in an effort to make you break the rule.

For members of the mafia, it is clear how this rule functions; if you are arrested you do not reveal any information, even if this means you end up in prison for much longer than you would if you talked. In return, your family will receive financial support throughout your detention (these funds usually come from protection rackets). If, on the other hand, you decide to break omertà, at best your family will be ostracised and left to fend for themselves; at worst somebody from the family will be killed.

The effect of omertà, however, extends well beyond the boundaries of mafia criminal organisations themselves and pervades the social fabric. So, how does it affect an ordinary person in everyday life? Let’s look at a practical example: paying the so called “pizzo” as victim of a protection racket.

Say you are a shopkeeper, or any other kind of small business enterprise. One day somebody turns up in your shop, or office, and asks for a “donation” to help the family of “friends” who are in prison. This is a typical approach used by mafiosi when extorting money in the form of a protection racket, as mentioned above. You have three choices: cough up the money, which will then become a fixed monthly obligation; refuse to pay; contact the authorities.

Needless to say, the majority of peope who find themselves in this situation opt for the first choice out of fear. Perhaps, they illude themselves that after a while the money will no longer be demanded, that they will have paid their “debt.” What actually happens, of course, is that the sum required increases until you can no longer afford it. Then, you are left with the other two choices in any case.

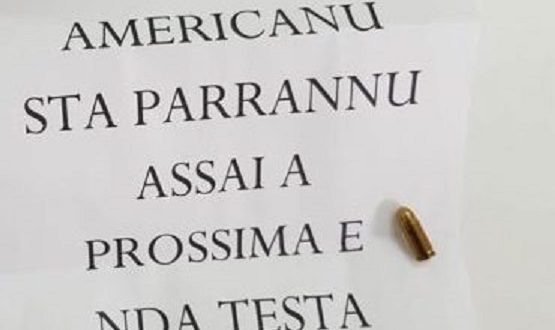

When somebody refuses to pay (or can no longer afford to pay), they start to receive threatening phone calls, or calls in person. Things will then progress to having the entrance to your shop or business set alight or your car burnt out. Many persist with omertà even at this stage. When police investigate the reason for the fire, the victim insists that they have never received threats or requests for money. Other common forms of threat are receiving a bullet in an envelope by post or finding a goat’s head on the bonnet of your car or outside your front door (goats are cheaper than horses).

In the end, either people eventually turn to the authorities because they see no other way out or the authorities discover the extortion because of a fire or another form of threat and investigate independently. So, why do so few people report attempted extortion? It is not just fear. The omertà mentality is so deeply-rooted that it is their first instinct not to report. If they turn to relatives and friends, the advice they get will be overwhelmingly to give in to the demand. DIstrust of the state and any form of authority is a longstanding and stubborn attitude among Sicilians and the state itself has historically done little to fight it.

The bombings of 1992 and the sacrifice of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino undoubtedly marked a turning point. Their example of courage and service sparked a renaissance of social conscience in Sicilian society. Shopkeepers and business owners got organised into groups opposing the “pizzo,” offering financial and legal support to those who reported attempted extortion. Schools became a frontline in educating children in the need for legality; as Sicilian writer and poet Gesuldo Bufalino said,

“the mafia will be defeated by an army of primary school teachers.”

There is still a long way to go. Too often investigators uncover protection rackets with dozens of victims, none of whom have ever reported anything. We need only remember that Matteo Messina Denaro remained at large for 30 years, living quite openly, at least for the last 4 of those years, in a small town in the Province of Trapani.

I have used protection rackets as one of the most common examples of where omertà comes into play. However, anybody can find themselves in a situation where they have to decide whether to “talk” or look the other way; for example, something which happens in their workplace or something which they witness by chance. I myself have been in such a situation.

In the 1990s, when the University of Messina was described as a “verminaio”1 the first thing we did when we had exams was to look at the list of candidates looking for "notable" surnames from particular towns or villages so we were prepared for any eventuality.

I will end this piece with a story, also from Messina, of a brave man, who challenged the logic of omertà at a time when few dared do so. In his case the state not only failed to protect him but, thanks to another “verminaio”, the Messina Court of Appeal, also sullied his name after his death.

Ignazio Aloisi is a security guard working in an armoured van collecting takings from toll booths on the Messina-Palermo motorway. On 3 September 1979 his van is ambushed by armed robbers at a toll booth near Messina. No shots are fired and the robbers get away with the cash

Aloisi has noted the registration number of the getaway car and seen the face of one of the assailants. Most people would just feel lucky to have survived the experience and say nothing to complicate their life but Aloisi gives this information to investigators

Aloisi identifies the man he saw from a police photo and in person: Pasquale Castorina, a member of the Costa mafia clan in Messina. By the time the investigating Judge summons him to confirm and sign his statement on October 24, threatening phone calls are already arriving at Aloisi’s home.

Nonetheless, Aloisi confirms and signs his statement and waits for the trial to start. The Byzantine procedures of Italian justice mean waiting more than a year, during which threats and pressure to retract continue.

The night before his testimony in court, on 7 November 1980, Aloisi works a night shift and, as he opens his front door on his return at 6.30 a.m., a shot is fired at him by a man on motorbike but just misses him.

Despite all this, Aloisi gives evidence in court and Castorina is sentenced to 8 years' imprisonment. On his release he decides to take his revenge but bides his time so as not to make it seem too obvious that he is responsible.

On Sunday 27 January 1991, Aloisi and his 14-year-old daughter attend the Serie B football match between Messina and Verona. At the end of the match, together with a group of friends, they head home on foot as they live quite near the stadium.

Suddenly, a masked man appears from nowhere out of the crowd armed with a pistol and fires 3 shots at Aloisi in front of his terrified daughter and friends. One hits him in the chest, another in the head. He dies instantly.

For 2 years investigations bear no fruit until 3 mafiosi who have begun to collaborate with the authorities give seperate but concording versions of the events. Castorina and his wife's nephew are arrested for the murder, Castorina for ordering it & the nephew for carrying it out

On 15 April 1994, the 2 men are sentenced to 26 years in prison for the murder of Aloisi. They appeal against the conviction (in Italy, both prosecution & defence have automatic right to appeal) and at the appeal trial they change their strategy.

Instead of pleading innocence they admit their guilt but Castorina claims, without any evidence at all to back it it up, that Aloisi was a member of the gang that robbed the armoured van, acting as an 'insider'.

According to Castorina, Aloisi turned them in because he was unhappy with how the cash had been shared among the members of the gang. The judges believe him simply because Aloisi and Castorina lived very close & must therefore have known each other.

To no avail Aloisi's wife and daughter testify that he did not know Castorina and they had never heard of him either before the robbery. Castorina is found guilty but has his sentence reduced by 4 years. However, the judgment recognises Aloisi as a participant in the robbery.

Not only is this a scandalous libel of an innocent and very brave man* but it has serious practical repercussions for the family (*the Messina Court of Appeal was at the centre of numerous 'scandalous' judgments in favour of mafia suspects in 1980s & 1990s)

Once the judgment becomes definitive Aloisi's family have no right to compensation or other benefits available to families of innocent victims of mafia because he is no longer considered 'innocent'. Their battle to clear Aloisi's name continues to this day.

An untranslatable word, meaning literally a “bed of worms”, “pit of worms” or “nest of worms”, used to describe a place or institution pervaded by corruption and malpractice.