The murky background to Berlusconi's rise to power

Cosa Nostra, 'ndrangheta, neo-fascism and deviant elements of the state

On 18 January 1994, 'ndrangheta murders two Carabinieri, Antonino Fava & Vincenzo Garofalo on the A3 motorway, near Scilla in Calabria. Here I look at how this brutal crime ties in with Cosa Nostra’s bombing campaign of 1992-93, the collapse of Democrazia Cristiana and other traditional Italian political parties and Silvio Berlusconi's rise to power.

Much of what is written here has been established in the the judgment handed down by the Reggio Calabria Corte d'Assise in July 2020, sentencing Giuseppe Graviano and Rocco Santo Filippone to life imprisonment for ordering the murders of the two Carabinieri & other attacks. It is important to specify that this judgment is subject to an ongoing appeal. Other information has been confirmed by other court judgments. Anything not established by courts is indicated as such.

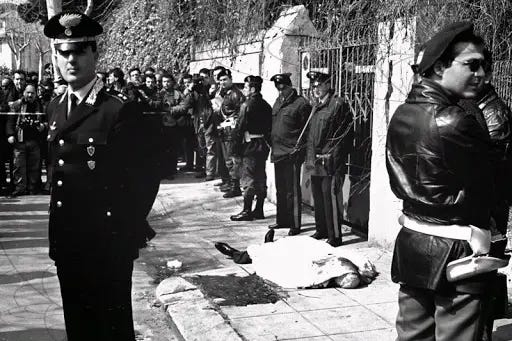

Murder of the Carabinieri

Just before 9.15 p.m. on 18 January 1994, the Carabinieri command centre in Palmi receives a radio message from Vincenzo Garofalo, patrolling the A3 motorway with his colleague Antonino Fava in their Alfa Romeo 75, saying that they are being followed by another car. The radio operator asks him to keep them updated on the situation but no further messages are received. Shortly afterwards, two Guardia di Finanza officers passing by chance find the Alfa Romeo on the hard shoulder, riddled with bullet holes, with the two Carabinieri dead inside.

At first, investigators concentrate on a specific line of inquiry. The same afternoon, Fava & Garofalo escort a group of magistrates from Messina to the prison in Palmi, where they are to question a 'pentito' (an offender assissting investigations) from Messina held in custody there. At 8.15 p.m., the Carabinieri return to the prison to escort the magistrates to Villa San Giovanni to take a ferry back to Messina. However, the magistrates tell them their questioning will continue for 2 hours extra, so they're ordered to patrol the motorway in the meantime. Maybe the magistrates were supposed to be the target. Maybe 'ndrangheta was doing a favour for their neighbours across the Strait, warning the 'pentito' to keep his mouth shut. As it turns out, it is a 'favour' but not for the mafia in Messina and for very different reasons.

As sustained by the Prosecution in the trial of Graviano and Filippone, and confirmed in the judgment, 'ndrangheta is doing a favour for Cosa Nostra, as part of Totò Riina's "strategia stragista" (carnage strategy) aimed at destabilising the Italian state. Riina was arrested a year earlier, on 15 January 1993, but his strategy is being continued by others, such as Graviano and Matteo Messina Denaro (finally arrested on 16 January 2023, after 30 years on the run).

Cooperation between Cosa Nostra and 'ndrangheta is shown by the conviction of Graviano (a member of Riina's Corleonesi) and Filippone (a member of the Piromalli 'ndrina). Both groups could benefit from a destabilised state structure leading to radical change in the political system.

Political and institutional turmoil

The Italian political system is in turmoil in January 1994, as the 'mani pulite' investigation, led by Antonio Di Pietro, continues to uncover corruption involving politicians, public officials and business people, leading to a crisis of trust in traditional parties.

Institutional instability is also a result of the state's inability to deal with Riina's carnage strategy throughout 1992 and 1993. At one stage, as part of its war on the state, Cosa Nostra attempts to infiltrate state institutions in Sicily by sponsoring its own political parties.

As early as 1989, with the founding of 'Lega Meridionale', then in 1990/91 other parties such as 'Sicilia Libera', Cosa Nostra agitates political waters campaigning for greater Sicilian autonomy. Graviano is tapped on one occasion saying 'Sicilia Libera' would make Sicily a tax haven.

These parties contain elements from the P2 masonic lodge (e.g. Licio Gelli), neo-fascism (e.g. Adriano Tilgher) & Cosa Nostra (e.g. Vito Ciancimino) and are partly modelled on the successful Lega Nord, whose leading ideologist Gianfranco Miglio is another of their sponsors behind the scenes. Miglio is considered the founding father of Lega Nord. He supported extreme federalism and had a strange attitude to the mafia, even arguing that autonomous southern regions should "maintain" the mafia, 'ndrangheta, camorra etc. & "institutionalise" them.

Article 416-bis and the Palermo Maxi-Trial

Significantly, these small parties support abolition of Art. 416-bis Italian Criminal Code introduced in 1982. This punishes membership of a "mafia-type organisation" with minimum 10 years' imprisonment & increases sentences for crimes committed to benefit the organisation. Art. 416-bis allows the Antimafia Pool of magistrates in Palermo, led by Antonino Caponnetto & including Giovanni Falcone & Paolo Borsellino, to hold the maxi-trial against 475 mafiosi in 1986-87 (see my previous Substack piece).

Art. 416-bis fundamentally alters the balance of power between mafia and state leadimg to the historic judgment in the maxi-trial, which is the first to demonstrate the existence of Cosa Nostra as an organisation with a centralised command & control structure.

Now, Cosa Nostra is about to exhibit the power and effectiveness of its command & control structure by literally going to war with the Italian state, already in political upheaval. Politically, the added tension & unrest will benefit one person in particular: Silvio Berlusconi.

Launching the carnage strategy

The initiative with Sicilian autonomist parties, mentioned above, has limited success, and Cosa Nostra grows increasingly frustrated with traditional parties showing no intention of scrapping Art. 416-bis & with the outcome of the maxi-trial being largely upheld on appeal. The decisive date is 30 January 1992, when the Supreme Court of Cassation confirms the convictions of the Appeal Court and overturns most of the acquittals, sealing the state's victory over Cosa Nostra. Riina realises this is a watershed & unleashes his desperate and insane .carnage strategy.

The first victim of this carnage is Christian Democrat Salvo Lima, killed in front of his villa in Mondello on 12 March 1992. Lima is Giulio Andreotti's man in Sicily, Cosa Nostra's link to Rome. The Christian Democrats have been in government constantly since 1944. Lima’s murder sends the message that the Christian Democrats are no longer of any use to Cosa Nostra. They have not been able to influence the maxi-trial or abolish Art. 416-bis. Now, the traditional parties are on the wane and the mafia needs to find new political allies.

The next step in the terror campaign is the elimination of Giovanni Falcone on 23 May 1992 at Capaci. This is partly as 'punishment' for being the man who instigated the maxi-trial & partly because he is set to become the first National Antimafia Prosecutor, thus he remains a serious threat. 57 days later, Paolo Borsellino suffers the same fate.

These spectacular bomb attacks completely disorientate the state. As well as the two antimafia magistrates, Falcone's wife, Francesca Morvillo, and 8 police protection officers die, including the first female Italian police officer ever to die on active service, Emanuela Loi.

The next phase of what is basically a terror campaign, rather than being aimed at representatives of the state, targets Italy's hugely valuable & highly symbolic cultural heritage. In 1993, bombs explode in Florence, Rome & Milan, killing ten people.

Ties between Cosa Nostra, neo-fascism and elements of the state

Before dealing with the bombs of 1993, a slight detour to look at the shady figure of Paolo Bellini, the person through whom the state learns of this change in strategy by Cosa Nostra. Bellini illustrates the link between neo-fascism, mafia & deviant parts of the state. Bellini is a neo-fascist activist who undergoes military training in Portugal in the early 1970s and then carries out political murders in Italy. He seems to benefit from some form of protection and is able to hide in South America until he returns to Italy in 1977.

On 2 August 1980, neo-fascists carry out the worst terrorist attack in postwar Italy when a bomb explodes at Bologna Station killing 85 & wounding 200 (see linked Twitter thread). Bellini has been convicted of taking part in the bomb attack and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Twitter thread on the Bologna Station bombing

Two days after the bombing, on 4 August 1980, police raid a hotel owned by Bellini's father near Reggio Emilia, as part of their search for known neo-fascist activists. They do not find Paolo Bellini but they do find somebody else who should not be there. It is Ugo Sisti, Chief Public Prosecutor at the Bologna Court. On a Monday morning, two days after a devastating terrorist attack in his jurisdiction, instead of co-ordinating inquiries from his office or on the spot, he is staying in a luxury hotel 50 miles away.

Nor is it just any luxury hotel, but one belonging to the father of a possible suspect for the terror attack, known to benefit from some kind of cover for his activity. Sisti suffers disciplinary consequences for his behaviour but a criminal trial ends with his acquittal.

Paolo Bellini is then arrested in February 1981 for theft (he is a renowned thief of valuable art works, as well as a killer). While in prison he becomes friendly with Cosa Nostra boss Antonino Gioè and, after his release, in 1991, he is asked to infiltrate Cosa Nostra.

The request to infiltrate Cosa Nostra, exploiting his friendship with Gioè, comes from Colonel Mario Mori of the Carabinieri Raggruppamento Operativo Speciale (ROS). Mori will later be involved in secret negotiations with Cosa Nostra.

Bellini infiltrates Cosa Nostra in 1991, just before the bombing campaign. He recounts how he learns of the strategy of targeting heritage sites when Gioè asks him, "how do you think you will feel if you wake up one day & the Leaning Tower of Pisa is no longer standing?"

The 1993 bombing campaign

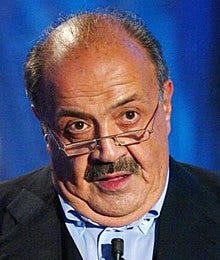

The first bomb attack of 1993, on 14 May, in via Fauro in Rome, is actually aimed at a person, not a heritage site. The target is TV chat show host Maurizio Costanzo (photo), noted for his antimafia stance, often hosting Giovanni Falcone on his programme.

The car bomb explosion leaves Costanzo & his wife Maria De Filippi, also a TV show host, uninjured, as Salvatore Benigno, the mafioso who detonates the bomb, does so a fraction too late, but 24 other people in surrounding buildings suffer injuries and damage is extensive.

Just after 1 a.m. on 27 May 1993, a car bomb explodes in via dei Georgofili in central Florence. The explosion causes the collapse of the Torre dei Pulci and the death of 5 people, 4 of whom are members of the family of the caretaker of the Tower. 48 people are injured. In addition several paintings in perhaps Italy's most famous art gallery, the Uffizi, adjacent to the explosion site, are badly damaged, some beyond repair. Fortunately, protection glass avoids damage to the most important works, but the shock felt in Italy is considerable.

At 11.15 p.m. on 27 July 1993, in via Palestro in Milan, a car bomb kills 5 people, injures 12 and seriously damages the Contemporary Art Gallery. The dead are a policeman and 3 fire officers who are inspecting the car from which smoke is rising and a homeless man sleeping on a nearby bench.

The same night, just a few minutes after midnight, two car bombs explode in Rome, one near the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano & another near the Church of San Giorgio in Velabro. Nobody is killed in these attacks but 22 people are injured.

Investigations into the role of Marcello Dell’Utri and Silvio Berlusconi

According to the 'pentito' Pietro Riggio, the 'brain' behind the bomb attacks of 1993 is Marcello Dell'Utri, long time business associate and right-hand man to Silvio Berlusconi. Dell'Utri & Berlusconi are investigated in the 1990s for possibly ordering the attacks.

That investigation comes to no conclusion but magistrates in Florence have now reopened investigations following affirmations made by Riggio & Giuseppe Graviano during the trial in Reggio Calabria for the murder of the Carabinieri with which the this piece started.

Of course, as Falcone taught us, affirmations made by 'pentiti' have to be subjected to the most rigorous verification before they can be trusted. In Graviano's case, he is not even a 'pentito'. Investigations must take their course and when mafia is involved they are complex.

Marcello Dell'Utri is sentenced to 7 years in prison in 2014 for aiding & abetting the mafia, after a long court case involving two appeals & two Supreme Court of Cassation rulings. The Courts find that he acted as an intermediary between Cosa Nostra and Berlusconi up to 1992.

According to the court, Dell'Utri's activities constitute "a voluntary, conscious, specific & precious contribution to the maintenance, consolidation and strengthening of Cosa Nostra ..." Dell'Utri's mediation offers Cosa Nostra "the opportunity to come into contact with important sections of the economic & financial world, thus favouring the pursuit of its illicit aims, both economic & political." Moreover, "there is proof that Dell'Utri promised specific political benefits to the mafia, in exchange for which the mafia undertook to vote for Forza Italia at the earliest electoral opportunity."

The same court judgments also find that Berlusconi pays large sums of protection money to Cosa Nostra for a period of 18 years from 1974 to 1992. It is possible that he continues to do so up to 1994, even after becoming PM in March of that year, but this is not proven. On this point the judgment reads, "refusing to seek official help (which seems never to have crossed his mind), [Berlusconi] sheltered beneath the umbrella of mafia protection, employing Vittorio Mangano at Arcore & never avoiding the obligation to pay huge sums to the mafia in exchange for protection."

Negotiations between Carabinieri and Cosa Nostra

Earlier in the thread we mentioned secret talks between state & mafia. These take place in the aftermath of the Capaci attack that kills Falcone & continue after Borsellino's murder. They are conducted by Carabinieri officers Mario Mori, Antonio Subranni & Giuseppe De Donno. The three officers are tried for this, together with Marcello Dell'Utri & sentenced to 12 years' imprisonment in 2018. In 2021, however, the Court of Appeal acquits them all, Dell'Utri "per non aver commesso il fatto", the Carabinieri "perché il fatto non costituisce reato". In other words, the court finds that Dell'Utri is not involved in the negotiations, while the Carabinieri do negotiate with the mafia but this does not constitute a criminal offence. This judgment now awaits confirmation by the Supreme Court of Cassation.

Cosa Nostra has high expectations of these negotiations but when they come to nothing they turn their anger on the Carabinieri. To make things worse, the Carabinieri from ROS, the section to which the 3 officers belong, capture Totò Riina on 15 January 1993 in Palermo.

Thus, we return to the murder of the two Carabinieri with which this piece opens. As well as this crime, 'ndrangheta carry out two similar attacks on Carabinieri in Calabria on behalf of Cosa Nostra, one in December 1993 (no injuries), the other in February 1994 (two wounded).

The final & most dramatic attack on the Carabinieri is planned to happen at the Olympic Stadium in Rome, this time to be carried out by Cosa Nostra and, due to the circumstances & timing of the event, the names of Marcello Dell'Utri & Silvio Berlusconi reappear in the story.

Failed Olympic Stadium bombing and Berlusconi’s entry into politics: is there a link?

All of the bomb attacks of 1993 take place outside Sicily. Indeed, they are carried out in major cities of central-northern Italy against cultural heritage targets with a probability of causing innocent civilian casualties. But they are relatively limited. So why exactly?

According to Gaspare Spatuzza, a Cosa Nostra 'pentito', who has admitted involvement in every attack of 1992 & 1993, it was explicitly a campaign of terrorism, aimed at disorientating & frightening public opinion. Again, why? What did Cosa Nostra hope to gain?

Spatuzza distinguishes between the attacks against Falcone and Borsellino in Palermo and those on the mainland in 1993. The former are attacks against enemies of Cosa Nostra, the latter are pure terrorism. He learns the reason behind this terror campaign from Giuseppe Graviano.

It should be specified here that we only have Spatuzza's word for what follows. Graviano denies it. Consider, however, that Graviano remains in prison subject to the art. 41-bis regime as he refuses to collaborate and just drip feeds occasional, often cryptic, pieces of evidence.

Spatuzza, on the other hand, has demonstrated contrition and fully cooperated with investigators. It should be remembered that collaborating with an investigation in Italy does not give you immunity from prosecution, offering just a partial reduction to any sentence received. He has been held to be reliable as, in most cases, his testimony has been proved accurate (in some others it has not been possible to prove but in no cases has it proved false) and he has consequently been admitted to a protection programme.

Spatuzza recounts that he meets Giuseppe Graviano on Saturday 22 January 1994 in Bar Doney on Via Veneto in Rome. Graviano is ecstatic, as if he has won the lottery. He says they have got everything they wanted from the people for whom they have been carrying out these bombings. He says that these people are serious, not like the Socialists who they voted for in 1988-89 and who then waged war on them. When Spatuzza asks who these people are, Graviano tells him Dell'Utri and Berlusconi. Spatuzza asks if he means the owner of Canale 5 & Graviano confirms.

Graviano says that, thanks to these people, we have the country in our hands. The date of 22 January is significant because a final devastating bomb attack is planned for the next day, Sunday 23 January 1994, at the Olympic Stadium in Rome, where Roma are playing Udinese.

The main target of this attack is again the Carabinieri. Explosives are prepared and transferred to Rome over several months in 1993, where they are packed into a Lancia Thema in a rented garage. There is no fixed date for the attack until Graviano tells Spatuzza to hurry. He says the attack must happen on 23 January because something important is going to happen the next week. Spatuzza and the other members of his group have inspected the area and prepared their plan, which is now set in motion.

This site chosen is in Viale dei Gladiatori as it is where Carabinieri gather at the end of matches to control the crowds leaving the Stadium. When inspecting the area, the mafiosi have seen that a coachload of Carabinieri arrive here at 4.30 p.m. on matchdays & they plan to set off the bomb then. Pieces of metal and bolts have been packed in with the explosives to cause maximum carnage. Gaspare Spatuzza and Salvatore Benigno ride a motorbike up onto Monte Mario hill behind the stadium from where they get a good view. They have a remote control to detonate the bomb.

On cue, at 4.30 p.m., the coach carrying Carabinieri arrives. Spectators are already coming out of the stadium as the match draws to an end. Benigno presses the button. Nothing. He presses it again. Still nothing. Spatuzza, after he becomes a 'pentito', calls it a miracle.

On Wednesday 26 January 1994, Berlusconi makes his televised speech announcing his entry into politics with his new party Forza Italia. Is this the important event Graviano referred to?

According to an alternative theory, orders came down to abort the attack because of Berlusconi's imminent announcement. Spatuzza, however, has always stuck to his story of a malfunction.

If Spatuzza's accounts are true, Dell'Utri and Berlusconi are responsible for ordering a bombing campaign in order to create an atmosphere of instability and insecurity that would favour the arrival of a new party on the political scene, promising to 'save the nation' from disorder and chaos. Moreover, not content with the 10 lives taken during the bombing campaign of 1993, they are prepared to take dozens of other lives that would have been lost if the car bomb outside the Olympic Stadium had exploded.

The day after Berlusconi announces his entry into politics, on Thursday 27 January 1994, Giuseppe Graviano is arrested in Milan.